Three years ago I began visiting two migratory bird sanctuaries on the northside of Chicago: the Montrose Point Bird & Butterfly Sanctuary (aka the Magic Hedge) and the Bill Jarvis Migratory Bird Sanctuary. My first visits were spontaneous, I was seduced by the dense greenery of the spaces along Chicago’s lakefront where the landscape is otherwise mostly mowed lawns and meadows. Encounters at these sites were not limited to the hundreds of more-than-human species found within. After locking eyes with a couple of men, it rapidly became apparent to me that these were cruising grounds. Subsequent visits had ulterior purposes. Sometimes I was there for a quick head, other times to observe the birds, plants and insects. I sensed that my indeterminate presence confused other visitors. The bird watchers were cautious of me and the cruisers shied away from my camo t-shirts. I found this obscurity and versatility liberating.

This history of Montrose Point’s current incarnation begins in the 1950s when it was strategically chosen by the United States Army for a short range anti-aircraft Nike missile installation. Positioned in the middle of the city in anticipation of a speculative Soviet airstrike, the area was concealed by a security fence which was in turn covered by a hedge of non-indigenous Honeysuckle shrubs. The Army abandoned the site in 1969 and the fence was removed, but the Honeysuckles remained, retired from their duty as camouflage devices. After it was reclaimed as a public park in the 1970s, it became evident that the area was a hotspot for migratory birds. The Honeysuckle bushes and trees are an attractive stopover on their long and arduous journeys. At Montrose Point, the birds rest on branches, feed on berries or insects, and then take flight to continue their thousand-mile migratory routes.

In the 1990’s the city wanted to restore Montrose Point to a savanna, the ecosystem that flourished in the area prior to its development in the 19th century. The plan was met with skepticism by some and was embraced by others. Birders were concerned that removal of the shrubbery and trees would scare their feathered friends away while preservationists were concerned about population declines of indigenous plants and animals. After conducting a participatory design process involving scientists, bird watchers, residents, beach-goers, and urban planners, the city managed to both preserve the hedge and create a healthy habitat for native species. However, this “inclusive” urban planning initiative left out a significant contingent in their deliberations. Since the site provides a degree of privacy in the public sphere, it is frequently utilized as cruising grounds for gay men. The cruisers were not consulted as patrons of the park—-rather they were branded as criminal intruders. They were subjected to frequent police raids and arrests in an effort to make the park “safer” for everyone else. The scare tactics failed. Even after the site was publicly exposed in the press it remained an active cruising ground.

Even though they have shared the same territory for decades, there remains palpable tension between the bird-watchers and the cruisers. Birders who visit the sanctuary try to distinguish themselves from the cruisers with visual signs. On online forums they advise each other to differentiate themselves by wearing obvious birding gear like bucket hats, binoculars, and patches on coats. Cruisers use similar tactics, creating and reading non-verbal codes of objects and body language—similar to observing the feather color, neck length, and call patterns of a bird to identify its species.

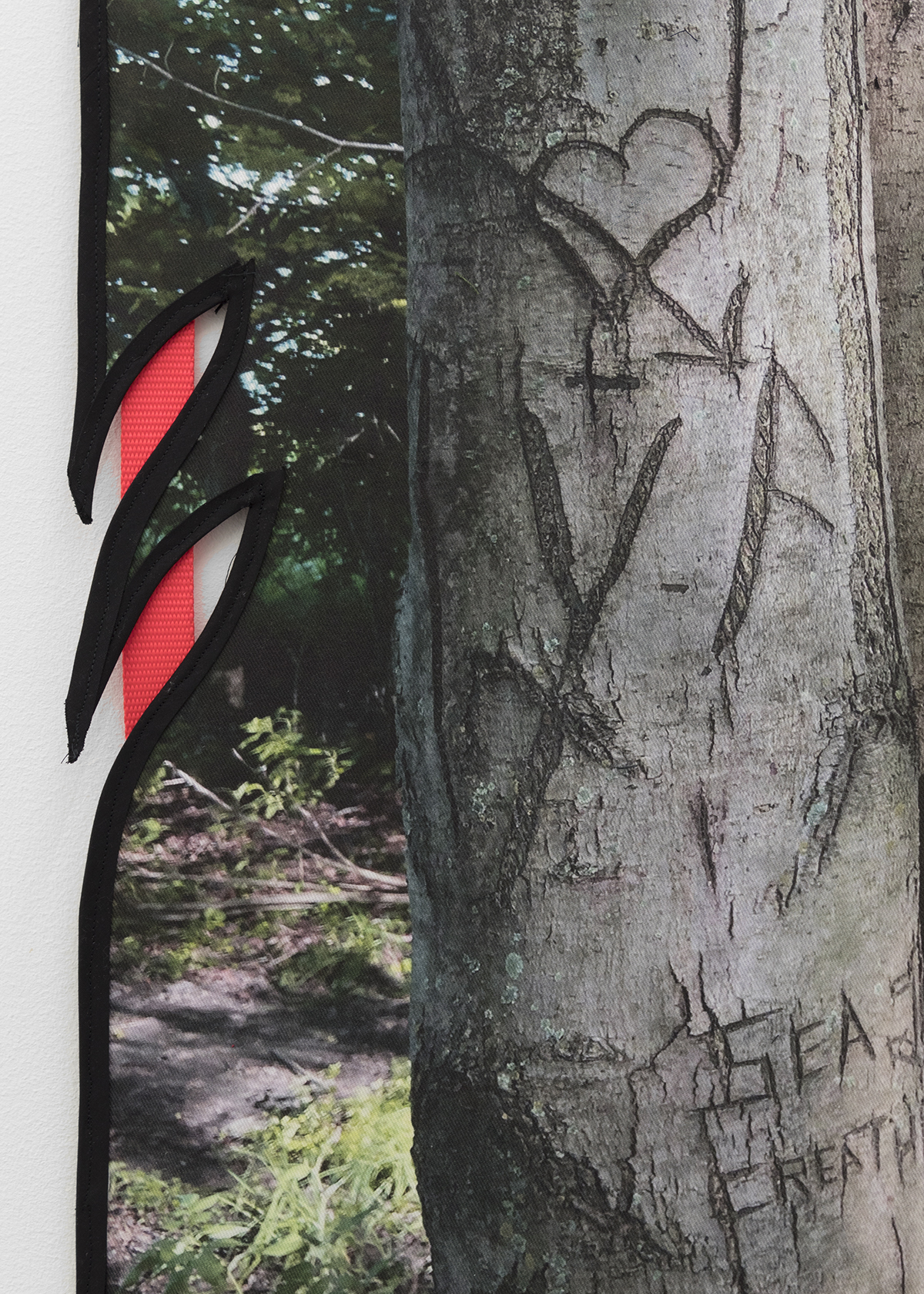

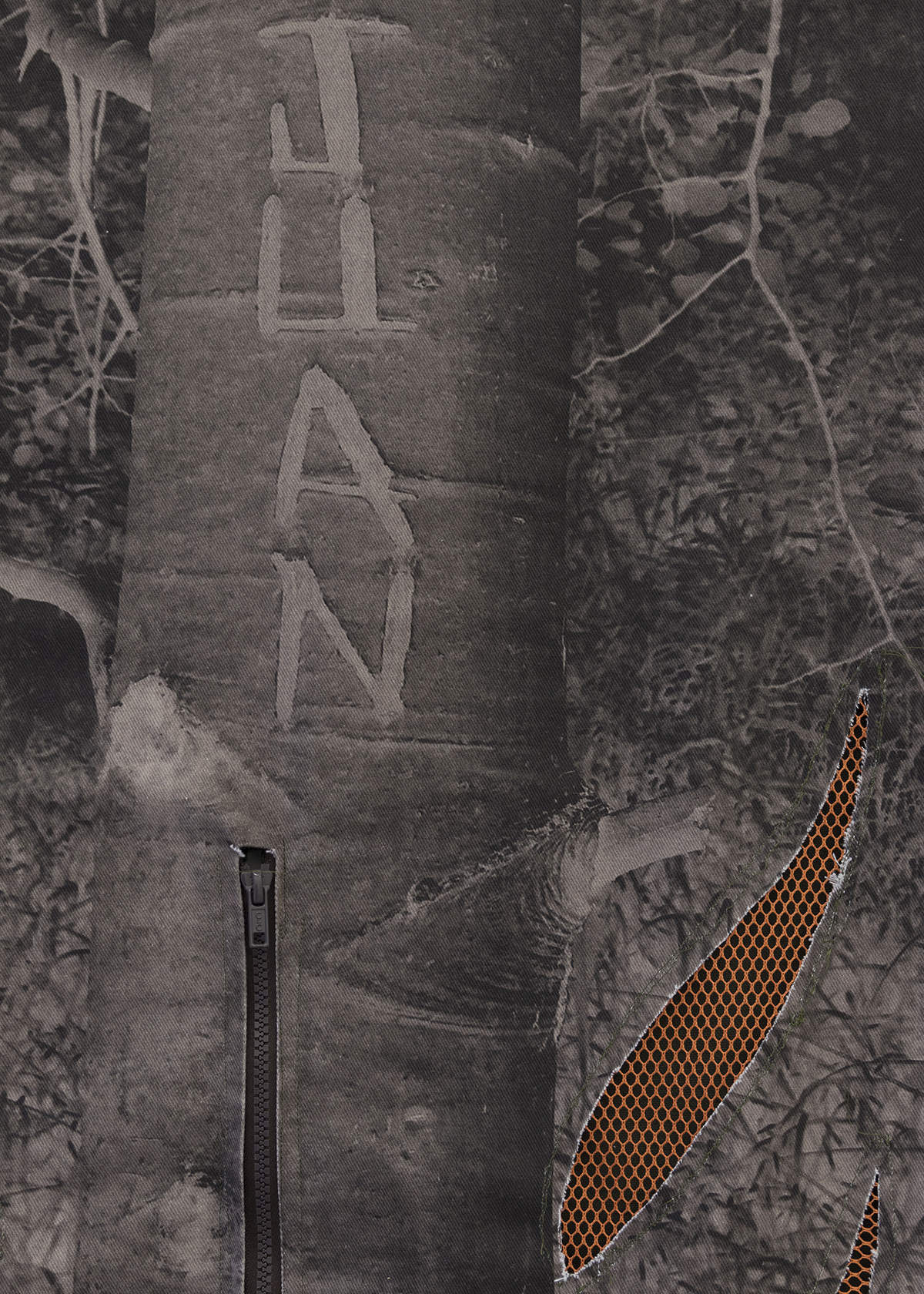

In my studio, I started to play with the forms, materials and visuals I encountered at the bird sanctuaries. I wanted to create a hybrid language that could signal multiple meanings and invoke different desires. The objects in this exhibition suggest function but they are not strictly instructional, they relate to and interact with both human and more-than-human bodies. There are moments of concealment and hypervisibility, recognition and confusion, seduction and repulsion. Just like messages carved into tree trunks by human hands, their legibility changes with perspective, knowledge, desire, time, and the intervention of other species. The exhibition is motivated by unexpected encounters of species, races, genders, sexualities and social classes in these bird sanctuaries. With this exhibition I try to think about conviviality, co-evolution and hybridity instead of documenting a historic reality.

- Faysal Altunbozar

Faysal Altunbozar (b. 1993, Istanbul) is an interdisciplinary artist currently based in Chicago. An MFA recipient from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, his work has been exhibited in Turkey, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United States.